In commemoration of Emancipation Day in Jamaica on August 1, over the next few days I will be sharing the wealth of history associated with the Free Village of Kitson Town and its environs in the parish of St. Catherine.

I didn’t know much about Kitson Town before April 2019. Which is a shame, considering how culturally rich it is. Fortunately, that month I carried a handful of intrepid photography students to explore Mountain River Cave. This was when I met members of the Kitson Town Community Development Committee (CDC), who introduced me to their village’s rich cultural heritage. I, in turn, am sharing this knowledge with you.

Free villages were communities established in Jamaica after Emancipation in 1838 for newly freed slaves, normally by abolitionist missionaries. They were located away from sugar plantations in order to prevent the plantations owners from exerting power over their former slaves by determining their living conditions. Kitson Town was established on July 3, 1841 on 195 acres of land that was purchased by the Baptist Missionary James Phillipo. It was named after George Kitson in an area formerly known as Red Hills, in the former parish of St. John.

Why am I focusing on Kitson Town? Apart from being a free village, Kitson Town is unique in that in a very small area, visitors are able to interact with in situ remnants of Jamaica’s history. These include pictographs and petroglyphs from pre-Columbian Taino Amerindians, legacies of slavery, buildings and artefacts from the colonial era, and built heritage from Jamaica’s post-emancipation and pre-independence era. The Kitson Town CDC is focused on using this rich cultural heritage to lay a foundation for its sustainable development.

Trodding with Tainos

As mentioned previously, my initial reason for visiting the environs of Kitson Town was to carry students to Mountain River Cave, which is designated a national monument by the Jamaica National Heritage Trust (JHNT).

Tainos were Jamaica’s first inhabitants, and were Amerindians that arrived from South America approximately 2500 years ago. They were a peaceable people who established villages throughout the island, cultivating crops such as cassava, maize and tobacco. Evidence of their activities are found across Jamaica, and one of the few places to view their pictographs and petroglyphs is at Mountain River Cave, located at Cudjoe Hill, which is approximately 30 minutes from Kitson Town. This is where we met our guide, Monica Wright.

From here we walked – or “trodded” as our Rastafarian brethren like to say. Trodding down some of the steepest steps I have ever walked, and then across the Mountain River. Then the hike really started – through limestone forests and over honeycomb rocks. Fortunately I was with a fun-loving set of students, a knowledgeable guide, her grandchildren and their dog, so the hour-long hike passed quickly. We were then able lay our eyes on artwork which experts have dated to between 500 to 1300 years old.

Early Europeans

In 1494, Spaniards led by Christopher Columbus landed in Jamaica. This represented the first recorded contact between Jamaicans and Europeans, and was an encounter that did not end well for the Tainos. I was taught in school that the Tainos were totally exterminated by the Spanish. However, this has recently been disputed, with one argument being that Tainos mixed with the Spaniard’s African slaves, resulting in Taino DNA being extant in some present-day Jamaicans.

The Spanish presence in Jamaica lasted until 1655 when British forces under the command of Admiral William Penn and General Robert Venables successfully captured the island from the Spanish. According to the Jamaica Information Service, the Spanish fled to Cuba and released their slaves. These slaves escaped into the mountainous interior and became the first Maroons, who were slaves that escaped from their colonial masters. The word originates from the Spanish word Cimarron, meaning wild. (More on the Maroons in Part II).

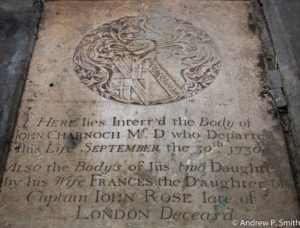

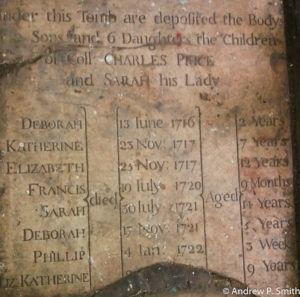

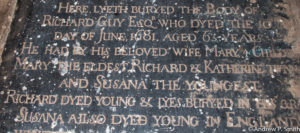

At St. John’s Anglican Church at Guanaboa Vale we discovered signs of this early European contact, including a whitewashed Spanish Jar of indeterminate age. What I found fascinating were the 17th and early 18th century graves of early British settlers, located on the floor of the church. These include the grave of Richard Guy who was buried at the age of 63 in 1681. The nearby community of Guy’s Hill is named after him. Other graves found here included that of: the seven children of Charles and Sarah Price, who passed on in the early 18th century, aged between 3 weeks to 14 years old, and John Charnoch, who died in 1730, and whose tomb is graced with heraldry.

There is so much cultural wealth in Kitson Town, that one post will not suffice. Coming in Part II….haunted ponds, subterranean tunnels and the ubiquity of shackles.